Cancer For decades, cancer treatment has largely depended on standard approaches like chemotherapy, radiation, and surgery. While these methods have saved millions of lives, they often come with significant side effects, incomplete tumour elimination, and the possibility of recurrence. However, a revolutionary new approach is approaching clinical reality—using living bacteria as targeted cancer-killing agents. This breakthrough idea is reshaping how scientists and doctors imagine the future of oncology. The goal is not only to destroy cancer more effectively but to do it with unparalleled precision and minimal harm to healthy tissues.

Table of Contents

Reengineering Bacteria to Fight Cancer

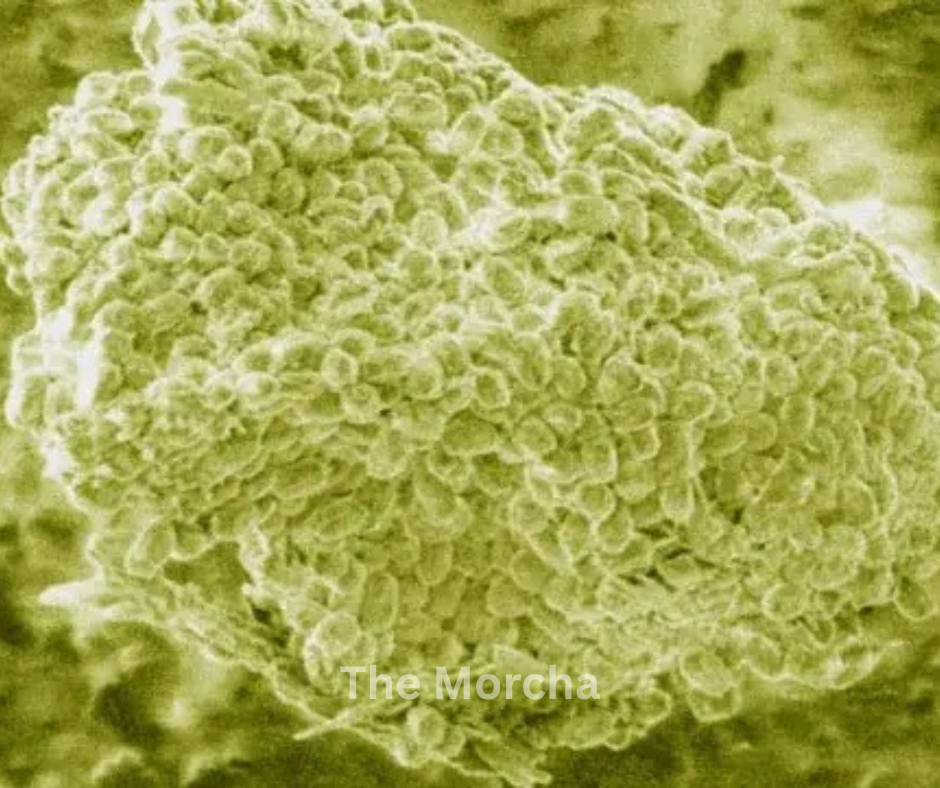

At first, the thought of injecting bacteria into a cancer patient might sound alarming. After all, bacteria are typically viewed as disease-causing microorganisms. But the very features that make them capable of entering and surviving in difficult environments are being turned into tools against cancer.

Researchers at the South Australian Health and Medical Research Institute (SAHMRI) are among the global pioneers exploring this concept. Their work builds on the idea that bacteria can be genetically engineered to locate tumours, deliver therapeutic substances exactly where they are needed, and then self-destruct after completing their mission. So far, more than 70 trials and over 500 scientific papers have explored different facets of such bacterial therapies—a sign of growing confidence in this developing field.

These engineered bacteria act like “smart drugs” that make precise, timed interventions inside the human body. Once inside a tumour, they release molecules that collapse cancer cells and simultaneously awaken the patient’s immune system—creating a double-pronged attack.

Why Scientists Are Moving Beyond Chemotherapy and Radiation

Traditional therapies, despite their success, suffer from inherent limitations:

- Toxicity: Chemotherapy and radiation do not distinguish between cancerous and healthy cells, often causing severe side effects like nausea, hair loss, and fatigue.

- Resistance: Some tumours develop resistance to drugs, making repeated treatments less effective.

- Poor penetration: Chemotherapy drugs sometimes fail to reach inner tumour zones lacking oxygen (hypoxic regions), leaving behind live cancer cells that later cause relapse.

- Suppressed immunity: Many treatments weaken the patient’s immune response, which is critical for long-term cancer control.

Bacteria-based treatments offer a unique way to address all of these issues simultaneously. Engineered bacteria can infiltrate even the deepest layers of a tumour, survive in low-oxygen environments, and carry “payloads”—specialized substances that destroy or weaken cancer cells.

How Engineered Bacteria Work

To work effectively, bacteria must be precisely programmed. Scientists modify their genetic code so that they activate only when they detect signals typical of tumour tissue—like low oxygen levels, unusual acidity, or certain metabolites. Once active, they can perform several cancer-fighting functions:

Selective tumour targeting

Certain bacteria naturally favour hypoxic or necrotic tumour regions over normal, oxygen-rich tissues. This selective accumulation helps them act as natural tumour seekers.

Direct cancer cell killing

Some bacteria produce toxins or enzymes that induce apoptosis (programmed cell death) or break down the tumour’s extracellular matrix, which makes cancer cells more vulnerable.

Immune system stimulation

The human immune system recognizes bacterial molecules—such as lipopolysaccharides and flagellin—as danger signals. Their presence provokes an immune alert, activating T cells and natural killer cells that join the fight against cancer cells.

Targeted drug delivery

When loaded with medication, bacteria can act as delivery vehicles. They release drugs, antibodies, or genetic material directly into cancer tissue, greatly reducing harm to healthy organs.

Self-destruction and clearance

To prevent uncontrolled bacterial growth or infection, scientists design self-destruction circuits. After completing their task, the bacteria undergo programmed lysis, leaving the body clean and safe.

Genetic Engineering: The Key to Control and Safety

This revolutionary concept depends entirely on how reliably genetic control mechanisms can manage bacterial behaviour. Recent breakthroughs have allowed scientists to “program” bacteria using synthetic biology principles. For instance:

- Genetic switches can make bacteria turn on or off in response to external triggers like light, temperature, or chemical cues.

- “Kill-switch” genes are added to ensure that bacteria destroy themselves after completing their mission, reducing infection risk.

- Bacteria can also be designed to adopt different life-states—free-moving or stationary—based on environmental signals.

- For spatiotemporal control (precise timing and positioning), researchers have even used near-infrared light to trigger bacterial activation deep inside tissues. This adds another layer of precision unavailable in traditional cancer drugs.

The Role of Probiotic Bacteria

Interestingly, not all bacteria used are foreign or harmful. Many belong to probiotic families already known to coexist safely in the human body, such as:

- E. coli Nissle: A harmless variant of E. coli found in gut probiotics.

- Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium: Found in yoghurt, vinegar, and fermented foods.

These familiar bacteria provide a safe foundation for therapeutic engineering. Their natural compatibility with human tissues makes them easier to manipulate without causing systemic harm. By equipping them with therapeutic genes, scientists can transform them into living micro‑factories that produce anti‑cancer molecules inside tumours.

Ongoing Research and Clinical Trials

The field has advanced swiftly from concept to application. Studies involving genetically engineered strains of Salmonella, Clostridium, Listeria, and E. coli have demonstrated strong tumour‑targeting capability in laboratory and animal models.

Clinical progress, although still early, is encouraging. Several ongoing human trials focus on testing safety, dosage, and tumour‑specific efficacy. The outcomes so far suggest that bacterial therapies could significantly complement existing treatments rather than replace them entirely. For instance, combining bacterial therapy with radiation or immunotherapy often enhances cancer suppression because bacteria reach regions that standard treatments cannot.

The Science Behind the Promise

Selective tumour colonization

Most solid tumours contain oxygen‑poor areas that ordinary drugs cannot reach. Certain engineered bacteria, however, thrive in precisely such environments, which allows them to colonize the tumour from within.

Synergistic treatment potential

Since bacteria infiltrate regions inaccessible to radiation or chemotherapy, combining these methods can cover the entire tumour more effectively.

Personalized immunotherapy

Because bacteria can be easily modified, they can carry immune‑stimulating molecules tailored to each cancer type or even individual patients.

Theranostic possibilities

Scientists are exploring “theranostic bacteria” that combine therapy with diagnostic capability. These bacteria not only treat cancer but also help in tracking tumour response through imaging signals.

The benefits of bacterial therapy are substantial

- High precision: Bacteria differentiate cancerous from normal tissue naturally, reducing off‑target effects.

- Low toxicity: Drugs stay within the tumour rather than circulating through the entire body.

- Immune awakening: Immune cells learn to recognize and attack cancer.

- Reaching inaccessible tumours: Bacteria can infiltrate deep, oxygen‑poor zones untouched by most drugs.

- Self‑limiting nature: Once the bacteria’s task is complete, self‑destruct circuits ensure safety.

These properties promise a future where cancer treatment becomes less painful, more targeted, and much more effective.

Pancreas, Lung, and Head & Neck Cancers

Some of the most challenging cancers to treat today are pancreatic, lung, and head‑and‑neck cancers. These tumours often resist chemotherapy and are located in regions that make surgery or radiation risky. Bacteria‑based therapies could play a key role in overcoming these obstacles.

- Pancreatic cancer: One of the deadliest cancers due to its dense, oxygen‑starved structure. Bacteria can navigate and multiply inside these hostile micro‑environments where drugs fail.

- Lung cancer: Bacterial therapy may offer targeted options for tumours deep inside lung tissue where drug delivery is difficult.

- Head and neck cancers: Because of their accessibility and frequent recurrence, these tumours are ideal candidates for localized bacterial injections.

Key Challenges and Risks

As exciting as the prospect sounds, several critical challenges remain before bacteria‑based therapy becomes mainstream:

Safety concerns: Introducing live bacteria into a patient must be done cautiously to avoid infection or sepsis. Even attenuated strains may pose risks to immune‑compromised individuals.

Precise control: Ensuring the engineered bacteria activate only within tumour sites is vital. Any leakage into healthy tissues could be harmful.

Immune system interaction: The body might eliminate helpful bacteria too early before they complete their mission.

Tumour diversity: Each tumour has unique conditions. A bacterial strain that works on one cancer type might be ineffective against another.

Manufacturing complexity: Producing genetically engineered bacteria under strict quality standards (GMP) is challenging and expensive.

Regulatory approval: Agencies must define new guidelines for living therapeutics, since bacteria behave differently from conventional drugs.

Addressing these issues requires continuous collaboration across synthetic biology, microbial engineering, and cancer immunology.

Global Research Landscape

Beyond Australia, teams in the United States, Europe, China, and Japan are pursuing parallel studies in bacterial oncology. Leading universities and biotech companies are exploring different bacterial species, genetic circuits, and payload designs.

Recent reviews published in top journals highlight bacterial immunotherapy as one of the fastest‑growing frontiers in cancer research. Although most studies are still at the preclinical stage, several phase I trials are evaluating modified bacterial strains for safety in humans.

The central idea remains the same: bacteria as living, self‑navigating, self‑terminating anti‑cancer agents—an entirely new class of biologic therapy.

Smarter genetic designs: Scientists are creating bacteria that sense multiple tumour cues simultaneously—such as acidity, nutrient deprivation, or hypoxia—so that activation is accurate and context‑specific.

Advanced payloads: Future bacteria may deliver not only drugs but also immune modulators, checkpoint inhibitors, or even CAR‑T cell stimulators directly into tumours.

Integration with nanotechnology: Hybrid designs combining bacteria with nanoparticles can support both therapy and imaging functions at once.

Personalized bacterial therapy: Using genomic and microbiome data, doctors could select bacterial strains best suited to an individual’s tumour characteristics.

Regulatory frameworks: New international protocols are being drafted to ensure safe clinical use, including real‑time tracking of bacterial behaviour inside patients.

When Could This Become a Common Cancer Treatment?

While the progress is impressive, the transition from laboratory to clinic will take time. Before bacterial therapies become routine, several milestones must be achieved:

Establishing safety: Phase I and II clinical trials must confirm that these therapies can be administered safely without infection risks.

Understanding dosage and combinations: Scientists must determine ideal bacterial quantities, delivery routes, and how best to pair them with existing treatments.

Gaining regulatory approval: Because these are living organisms with self‑replicating abilities, safety tests are more complex than for chemical drugs. Optimistically, initial approvals might appear within the next 5–10 years for limited cases such as untreatable or refractory cancers. However, widespread adoption across cancer types may require an additional decade or more.